Philonise Floyd – “The world is traumatized” is literally true

- 12 June 2021

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Generational trauma , News ,

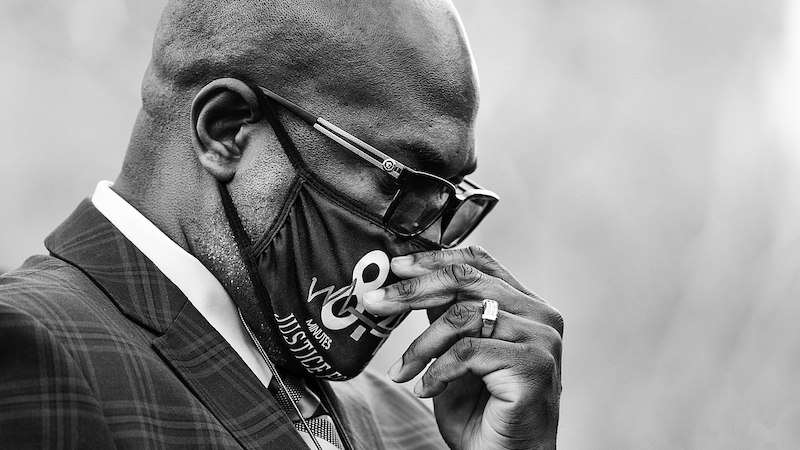

13 April 2021 was the 12th day of Derek Chauvin’s trial for the murder of George Floyd. Amid late winter snow flurries, his brother Philonise Floyd spoke outside the Hennepin County Government Center in Minneapolis. “The world is traumatized.”

If the world was to stop—just for a moment—and ask me what I had to say, I would repeat these four words. “The world is traumatized.”

If the world was to stop—just for a moment—and ask me what I had to say, I would repeat these four words. “The world is traumatized.”

The world is traumatized

Philonise Floyd’s words are among the most powerful ever uttered by mankind. They are the words we most need to hear, to reflect on, to act on. As we struggle with myriad issues from the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder to Covid-19, growing environmental, economic and geopolitical instability, these four words alone pinpoint the source of our problems.

The world is traumatized. Literally.

I don’t say this to diminish or trivialize the statement. I cannot begin to fathom what it’s like for George Floyd’s family to “watch a video of your loved one dying a thousand times.” I can’t even imagine going through a school system where every textbook has been written by a culture that’s different from mine and perceives itself as superior.

When I reiterate Philonise Floyd’s words, I don’t mean it in the way the phrase “all lives matter” has been used as a counterpoint to Black Lives Matter, implying global sympathy when it may mask a refusal to recognise institutional racism—and the racial trauma it perpetuates.

Racial trauma

I must admit it took me some time to grasp the extent and severity of racial trauma. Even though I’d been working through my own trauma and developing my understanding of its mechanics for some time, it wasn’t until the 2021 Intergenerational Trauma Conference that it landed emotionally.

Professor Kenneth V. Hardy spoke passionately and eloquently. He described racial trauma as “a by-product of perpetual exposure to oppressive conditions” that is “hardly ever acknowledged, almost never named”. The George Floyd uprisings “dared to make the implicit explicit.”

But what really hit me were Hardy’s ‘5 wounds of racial trauma’:

- Internalised evaluation—a constant sense of ‘not good enough’

- Assaulted sense of self—shaped by external toxic messages

- Learned voicelessness—an inability to advocate for oneself

- Rage—the “predictable product of a life of marginalisation”

- Psychological homelessness—no “sense of safety”

Third Culture Kid

I recognised these wounds in myself, mostly stemming from the first one—a deep sense of not measuring up to my grandfather, a WWI hero. Lacking the self-belief to listen to my own internal messaging, I tried—and failed—to shape myself in the ways the outside world advocated.

Lack of self-belief leads to lack of voice. Lack of voice leads to rage at the frustration and sense of impotence of being unable to change these “oppressive conditions”. These emotionally logical stepping-stones are intrinsic parts of the process of radicalisation.

In the George Floyd protests, I see the rage and frustration of racial trauma boiling over. Impotence is permanently overthrown. Whenever trauma is cleared, there’s an explosion of pent-up energy. It’s a natural part of the healing process.

Psychological homelessness? Tick. Partly the result of the first four wounds, partly from a childhood as a Third Culture Kid who was born in one country, grew up in three others and was a stranger in all four. The concept of ‘home’, as its commonly understood, means nothing to me.

Yet I found safety by delving into and healing these wounds.

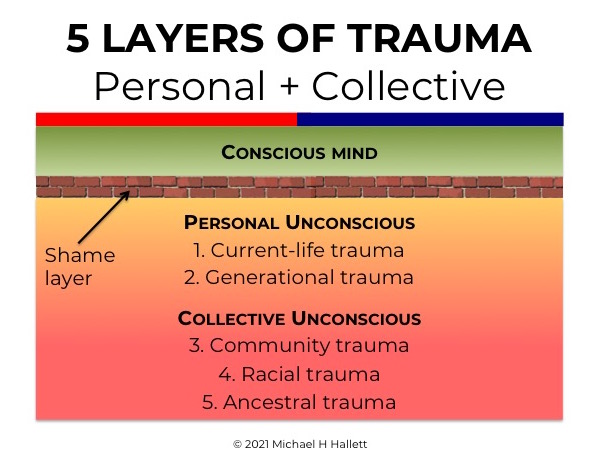

Five layers of trauma

What I discovered was a world of trauma. Ken Hardy’s vivid description of racial trauma and Peter McBride’s equally clear delineation of community trauma in Northern Ireland at ITC 2021 gelled with my own understanding to produce a five-tiered model:

- Current-life trauma—trauma from events in our current lifetime

- Generational trauma—trauma inherited from our immediate ancestors, typically from unresolved events that occurred to our parents and grandparents

- Community trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific community, such as ‘the troubles’ in Northern Ireland or India’s caste system

- Racial trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific race

- Ancestral trauma—trauma inherited from remote ancestors, up to several thousand years old, that affects everyone living in patriarchal societies

These five layers of trauma ripple through each other. They affect all of us—all of us—to different extents, depending on our genetic histories and current-life situations. Individually and collectively, trauma is inside us; yet, also, we unconsciously live inside a species-wide bubble of trauma.

The dividing line between our conscious minds and our trauma-driven behaviour is unconscious shame. Shame stuffs everything that we’ve repressed, rejected and denied about ourselves down into our unconscious then pours a layer of emotional concrete over it.

Saharasia

None of this exists randomly. The world isn’t accidentally traumatized.

Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd is the end result of thousands of years of trauma playing out, repeating from generation to generation. The further we get from traumatic events the harder attribution becomes. At ITC 2021 Peter McBride noted that it’s “difficult to link current phenomena with past traumas.”

Yet link them we can.

In Saharasia, geographer James DeMeo documents how drought, desertification and long-term famine in the Sahara, Arabia and Central Asia from around 4000 BC transformed peaceful hunter-gatherer and early agricultural societies into warring dynasties bent on conquest in the competition for increasingly scarce food and water sources.

DeMeo describes the profound psychological impact of famine:

“The very old and young were abandoned to die. Brothers stole food from sisters, and husbands left wives and babies to fend for themselves. While the maternal-infant bond endured the longest, eventually mothers abandoned their weakened infants and children.”

Three laws of patriarchy

Over time, this dog-eat-dog existence created trauma-based societies—the first patriarchies. At the heart of these new societies—which eventually conquered both the Old World and the New—are what I term the three laws of patriarchy:

- The Law of Masculinity states that the masculine rules the feminine

- The Law of Victimization states that the stronger can victimize the weaker to the extent that they can get away with it

- The Law of Otherness states that those who are ‘other’ can be victimized to the extent of their otherness

The overlap between these three laws created societies that engaged in racism, sexism, tribalism, homophobia and other forms of abuse. Trauma perpetuates through military, political, economic, legal and educational systems that favour the favoured—whoever the dominant class might be.

Peter McBride observes that there’s “trauma everywhere”. This causes the “normalisation of the abnormal”. For the last six millennia, humanity has dealt with its collective trauma by refusing to acknowledge it. No part of it has been more denied than racial trauma.

Ken Hardy notes that “when a phenomenon is not named, it is not acknowledged. When it is not acknowledged, it is not considered legitimate. When it is not considered legitimate, it’s hard to treat.”

Naming the phenomenon begins with Philonise Floyd’s words. “The world is traumatized.”

ONLINE COURSE

Image: Philonise Floyd outside the Hennepin County Government Center (CC BY-SA 2.0)