What is community trauma?

- 16 February 2021

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones , Generational trauma ,

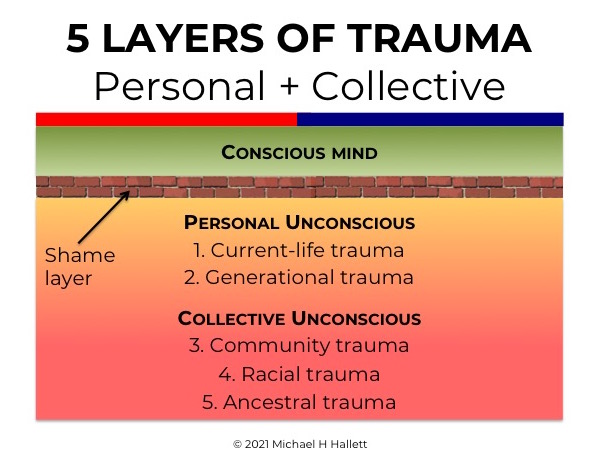

In Trauma exists as a series of ripples, I describe the multiple, interconnected sources of trauma that may exist in our lives. I’ve broken down these sources into five key layers. In this article I’m going to focus on the middle layer, community trauma.

Community trauma is trauma that affects an entire, specific community, such as “the troubles” in Northern Ireland.

First of all, let’s place this trauma in the context of the other key sources. All trauma is buried in our unconscious under a layer of shame and denial. Trauma can be personal (unique to us) or collective (shared with circles of others).

- Current-life trauma—trauma from events in our current lifetime

- Generational trauma—trauma inherited from our immediate ancestors, typically from unresolved events that occurred to our parents and grandparents

- Community trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific community

- Racial trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific race

- Ancestral trauma—trauma inherited from remote ancestors, up to several thousand years old, that affects everyone living in patriarchal societies

What is community trauma?

Community trauma is trauma that affects an entire, specific community.

Peter McBride spoke at the 2021 Intergenerational Trauma Conference about community trauma (a.k.a. “societal trauma”) in Northern Ireland. He described “a political system that reinforces the divisions of the past and is incentivised to do so.”

India’s caste system is a multi-layered trauma with genetically entrenched, unconsciously agreed victim/victimizer dynamics between social groups.

Societies defeated through conquest suffer community trauma. Anthropologist L. Bryce Boyer noted the impact of failed nurturing on Apache mothers: “[They] have a very limited sense of responsibility… the mother’s tenderness for her baby is based upon her bestowing upon the infant care she herself desires as an adult.”

Other examples include the LGBT+ and transgender communities, perpetually war-torn failed states, and impoverished communities. Its impact is threefold:

- Visible victims

- Indirect victims

- Residual societal impact

Visible victims

Amputees in war zones, people living in shantytowns or refugee camps. Alcoholics and known victims of sexual violence. Because their status as victims is visible, there can be recognition of their trauma and efforts made to relieve it.

Indirect victims

Very often these are the wives and children of the visible victims. Without even the recognition that visible victims receive, they suffer from the effects of poverty, alcoholism, and covert sexual violence. There is often very little appetite to even discuss gender-based violence, let alone heal it. This lack of recognition breeds resentment.

Residual societal impact

The traumatic event—e.g., “the troubles” in Northern Ireland—remains the dominant and defining event in the community. Peter McBride described how people in Northern Ireland are always looking for signals as to where another person’s sympathies lie. Politicians and leaders at all levels of the community exploit this unresolved trauma to attract support.

This creates a ‘politics of trauma’ where leaders are “incentivised” to foster division because they gain wealth, status and power from doing so. Donald Trump used this method to great effect in the 2020 United States presidential election.

Community trauma causes the “emergence of cultural shame”—a set of social conventions that categorises people as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ depending on whether they follow them. Those who fail to comply are shamed by those who do. The Northern Irish practice of kneecapping is an extreme form of cultural shaming.

Traumatised communities have a diminished ability to care for themselves or their environment. They have little ability to protect themselves against slash-and-burn farming practices, illegal logging, paramilitary organisations or strongman warlords. Environmental degradation fuels human degradation and vice-versa.

As Peter McBride simply sums up, “There is a malaise in society.”

Trauma as a communal identity

Trauma can become part of a communal identity. In chapter 17 of Genesis, God instructs Abraham to circumcise all the male Israelites. This physiologically traumatic rite became embedded in their identity and celebrated as a sign of their covenant with God.

Traumatised communities can be reluctant to release their trauma because that involves a painful and confusing loss of identity. The community becomes defined by its trauma and perpetuates it as an identifying reference or framework, a badge of honour.

Peter McBride speaks of “community efforts to keep these memories alive”. He notes that “traumatised people change the narrative they have about their own identity. They change the way they brought up their children.”

In The History of Childhood, Lloyd DeMause writes that “child-rearing practices… are the very condition for the transmission and development of all other cultural elements.” Once a community raises a whole generation of traumatised children, all memory of pre-traumatic life is erased and the trauma is institutionalised.

Traumatised adults raise traumatised children. The cycle becomes self-perpetuating.

As time goes on, the source of trauma becomes less evident. “Communities can eventually ‘forget’ or minimise the source of their trauma, while still exhibiting their embedded trauma identity,” says McBride. It becomes increasingly “difficult to link current phenomena with past traumas”. Difficulty increases “the further away we move from the direct experience.”

Resolving community trauma

McBride describes trauma as the “normalisation of the abnormal.” Resolving community trauma requires normalising the normal. This must be done without knowing what ‘normal’ is because, as noted above, its collective memory has been lost.

Another stumbling blocks is that “there is no agreement of a narrative of what happened.” As long as both sides cling to a black-and-white view that the other side is entirely to blame, trauma persists.

During their Long Way Down motorcycle tour from Scotland to South Africa, adventurers Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman visited the Kigali genocide memorial in Rwanda. Over 250,000 people are buried there after fighting between Hutu and Tutsi tribes in 1994.

Leaving the museum, McGregor asked the curator whether she was Tutsi or Hutu. She beamed and said, “I am Rwandan.”

In am indebted to Peter McBride, Director of the Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, for my understanding of community trauma.

Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash