What is racial trauma?

- 17 February 2021

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones , Generational trauma ,

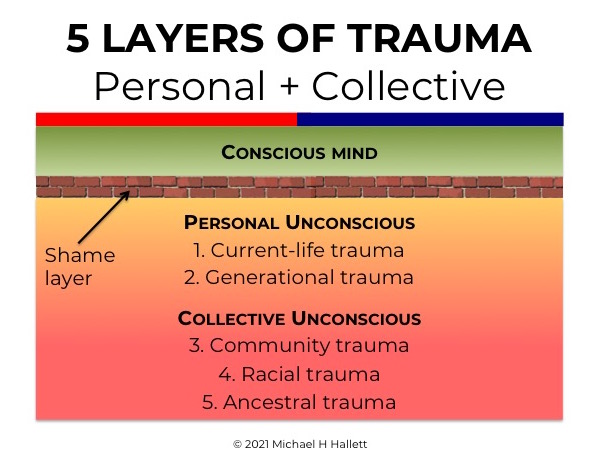

In Trauma exists as a series of ripples, I describe the multiple, interconnected sources of trauma that may exist in our lives. I’ve broken down these sources into five key layers. In this article I’m going to focus on the fourth layer, racial trauma.

Racial trauma is trauma that affects all people of colour, causing specific psychological wounds that are difficult to recognise and treat.

First of all, let’s place this trauma in the context of the other key sources. All trauma is buried in our unconscious under a layer of shame and denial. Trauma can be personal (unique to us) or collective (shared with circles of others).

- Current-life trauma—trauma from events in our current lifetime

- Generational trauma—trauma inherited from our immediate ancestors, typically from unresolved events that occurred to our parents and grandparents

- Community trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific community

- Racial trauma—trauma that affects an entire, specific race

- Ancestral trauma—trauma inherited from remote ancestors, up to several thousand years old, that affects everyone living in patriarchal societies

Recognising racial trauma

The deeper the level of the trauma (i.e., the higher the level number), the less recognisable—and the less recognised it is. Speaking at the 2021 Intergenerational Trauma Conference, Professor Kenneth V. Hardy noted that “we don’t even speak in terms of racial trauma.” It is “hardly ever acknowledged, almost never named.” This is because of the fog of shame and denial I mention above.

Hardy says that “when a phenomenon is not named, it is not acknowledged; when it is not acknowledged it is not considered legitimate; when it is not considered legitimate, it’s hard to treat.” The first steps are to recognise, name and describe racial trauma.

Based on my understanding and experience of several forms of inherited trauma, I’ll do my best to explain it from the outside in. I’ll also address its relevance to white privilege, the killing of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement.

What is racial trauma?

Kenneth Hardy describes racial trauma as “a by-product of perpetual exposure to oppressive conditions”. It is “like a toxic gas that we can’t see, we can’t touch it, but we know it exists and we know it’s destructive.”

The result is that people of colour “suffer a kind of unique suffering for which there is no language”. Hardy describes this suffering in terms of five wounds that “are invisible to the purveyors of those wounds”.

Wound 1: Internalised evaluation

Racial trauma causes people to feel devalued by broader society. As a coping mechanism they constantly evaluate themselves for shortcomings and find themselves wanting. This leads to a permanent sense of impostor syndrome. This in turn drives a constant quest for respect from the outside world to compensate for missing self-respect.

Wound 2: Assaulted sense of self

People of colour live in a society defined by white societal standards rather than being able to define their own appropriate standards. Their lives are shaped by toxic messages from a society that doesn’t understand or accept them, creating an “assaulted sense of self.”

In a recent example of toxic messaging, a British barrister described a student who was sent home from school because of her hair style as a “stroppy teenager of colour”. The barrister was defending school uniform policies. Those policies are intrinsically white and need to change. The barrister was later expelled from his chambers.

Wound 3: Learned voicelessness

Kenneth Hardy notes that racial trauma creates an inability to advocate for oneself. The trauma takes away the safety of speaking out. It’s a survival mechanism. Yet this “learned voicelessness” is also a pathway to both powerlessness and hopelessness, a dilemma between surviving and speaking up.

Wound 4: Rage

Hardy describes anger as an immediate reaction, while rage builds up over time when appropriate anger (at the first three wounds) cannot be expressed. It’s a “predictable product of a life of marginalisation.”

Hardy notes that rage is both simultaneously functional and dysfunctional. Repressed by voicelessness, rage is expressed through “myriad self-destructive behaviours,” often within the immediate family. “Rage has the power to destroy, but it also has the power to heal”. It can create a “fire in the belly” that ultimately explodes and drives social change.

Wound 5: Psychological homelessness

Kenneth Hardy describes ‘home’ as “where we feel a sense of connection, a sense of safety, a sense of comfort”. Racial trauma leaves its sufferers with no clear sense of home, because they don’t live in a society that accepts, encourages and nurtures them.

As I listened to Professor Hardy list these wounds, my understanding expanded. More importantly, my empathy for those suffering from racial trauma expanded. That’s because I’m intimately familiar with all five of these wounds, partly from generational trauma within my family and partly from a childhood as a Third Culture Kid. TCK’s are children who are born into one culture, grow up in another, and feel at home in neither.

It seems these wounds so clearly articulated by Hardy can be produced by other forms of trauma. They apply to Native American/Canadian peoples and Australian Aborigines. I don’t say this to minimise the suffering. I say it to recognise an empathic middle ground that helps us to help each other. As Hardy says, recognising trauma is a “game changer.”

Lack of connection, lack of safety, and lack of comfort are all ‘first circuit wounds’. In my experience, this relates to arrested development of the mother-child bond which causes a deficiency in emotional nurturing. The root cause of this transcends racial boundaries and goes as far back as the dawn of patriarchy, to what I term ‘the mother wound’.

George Floyd and Black Lives Matter

At ITC 2021 Kenneth Hardy said that the uprisings that followed the killing of George Floyd “dared to make the implicit explicit”. What I now see is that racial trauma was a key driver of the BLM protests that swept the globe in the summer and autumn of 2020.

Look at the following wounds: assaulted sense of self, learned voicelessness and rage. The brutal killing of George Floyd was ‘the stick that broke the camel’s back’. The “fire in the belly” reached boiling point and could no longer be contained. The voiceless found their voice. Once found, it can never be silenced.

In white social circles, people confronted the issue of white privilege. One way to think of it is as the absence of racial trauma—lacking the five wounds listed above.

How would you feel if you or your child was sent home from school because of your hair style, then described on social media by a senior member of the establishment, with a different ethnicity to yours, as “stroppy”? White privilege is never having to deal with such toxic situations.

Treating racial trauma

Hardy notes that, “There is no diagnosis for it, there is no recognition of it, and ultimately there is no treatment protocol”. Yet alleviation is possible. The first step is to recognise its existence. “There’s a value in naming racial trauma” because we avoid naming it to avoid dealing with it.

To recognise racial trauma “we have to change what we look for in order to change what we see”. Once we understand and empathise with its wounds, our perception shifts. Instead of “what’s wrong with you?”—which compounds the first wound, internalised evaluation—we move to “what happened to you?”

Once we ask this question, we discover a person who feels inherently devalued. Every step we take must “counteract devaluation” through increasing personal cohesion and resilience. Because, as Hardy observes, “There is no medication on the market for devaluation.”

In am indebted to Professor Kenneth V. Hardy for my understanding, incomplete though it is, of racial trauma.

Photo by Brian Lundquist on Unsplash

Thank you for summarizing Dr. Kenneth Hardy’s message that continues to shake me through my skin into my heart. Thank you thank you.

@Niparpon

Many thanks for leaving your message and I’m glad my post was useful.

It was a privilege to hear Dr. Hardy speak. He helped me understand not only my own trauma, but also Black Lives Matter and racial trauma as a global issue.

Best regards,

Michael