Living with ghosts – confronting generational trauma

- 16 March 2020

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Generational trauma ,

The first time I encountered generational trauma* I had no idea what I had hit. I had no idea I was living with ghosts.

Put simply, generational traumas are unresolved traumas that are passed from one generation to the next, where they surface as disempowering feelings and behaviours that make no sense to the person experiencing them. They are passed through a mechanism known as epigenetic inheritance. It’s effectively an inherited form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Anything traumatic or shameful is a potential source of generational sin: sexual impropriety, financial ruin, abandonment, and unexpressed grief. Ultimately, all trauma reflects the core separation at the heart of our being: the mother wound.

Despite the continuous presence of both my parents in my life, I struggled with feelings of abandonment from adolescence onwards. I could see them trying to build the best life for me—yet I was left feeling unloved and abandoned.

As these feelings intensified with age, I unconsciously found myself drawn—like many others—to researching my family tree. A lot of information came to hand fairly quickly: a swag of photographs inherited from my mother; a letter out of the blue from a long-lost cousin who was also researching her family’s past.

This is going to hurt

I realised I knew almost nothing about my father’s mother. She died in 1926 when my father was 4 years old. I ordered a death certificate so I could at least find out why she died. A message informed me the certificate would take about a week to arrive. During that week I had a vague thought it was “going to hurt,” but it had slipped my mind by the time the letter arrived.

I can remember the sound of the letterbox opening that day. Picking up the letter. Tearing open the corner. Then there’s a blank—I have no recollection of the following moments.

I can remember the sound of the letterbox opening that day. Picking up the letter. Tearing open the corner. Then there’s a blank—I have no recollection of the following moments.

The next thing I remember I was lying on the floor, in a foetal curl, howling in pain. I knew with absolute certainty this was not my pain. It was the pain of a 4-year-old boy who couldn’t grieve for his mother. The Great War had only ended a few years earlier. This was a culture that kept the upper lip stiff—i.e. emotionally repressed. My father was left feeling abandoned, angry and unable to grieve. He carried those feelings with him all his life and, with no framework for healing them, passed them on to me.

Principles

This single, simple example contains several principles for dealing with family ghosts:

- Expect the unexpected

- If you start digging, information will come to you

- This is old, compressed pain and it explodes on release

- This is not your pain, but it is your responsibility to clean it up

- It is not a linear process, but it is a sentient one

My father suffered further abandonment when his father remarried but later walked out on the marriage—and on his only son—and disappeared. The family was living in Bristol at the time.

Some time ago I felt drawn to a personal development workshop in Bristol. I didn’t think of my father’s past. I had just done one soul-searching exercise when I had the thought, “I’m in Bristol” and—just like the example above—the pain of his abandonment, over 80 years earlier, exploded into the open for healing.

Abandonment also featured on my mother’s side of the family.

* I used to call this ‘generational shame’ as that was the angle I encountered it from, but ‘generational trauma’ is a more encompassing and accurate term.

Living with ghosts

My grandfather Harold Blackburn was a pilot in World War I. He volunteered on the day the war broke out, 5 August 1914, and saw combat in France and the Middle East. He came home from the war and got married, but it didn’t work out.

My grandmother had an affair and everything blew up. My grandfather went to court for custody of my mother. In 1935, this was very unusual—but he won. My grandmother was ejected from the family and went to Cornwall with her second husband.

The shame of being abandoned by her own mother—who prioritised an affair over parenting her daughter—was absolutely crippling for my mother. Like my father, she never recovered. She spent the rest of her life living with ghosts and those painful feelings passed on to me.

War records

When I started researching my family, I was interested in my grandfather’s war records. So I searched the National Archives site to see what they had. I found some things of interest, but I also found my grandparents’ divorce papers. I didn’t give them much thought—but I put an item on my to-do list to go to the Archives.

A couple of years later the item was still there. So I put a date next to it… then another date, and a third. After missing that I sensed I was avoiding something. I picked a date I knew was free, put it on the calendar and committed to it.

From the moment I got up that morning, I hit obstructions. There were issues at home. I was late getting to the train. Finally, I got to London and caught the tube down to the National Archives. For those of you who are unfamiliar with them, the Archives are in London, just south of the River Thames before the Kew stop.

I decided that, as it was a nice day, I would get off at the previous stop and have a nice short walk over a bridge to the Archives. They don’t call it the Underground for nothing. I got off at Gunnersbury and found it was nowhere near a bridge. So I ended up walking about a mile and a half around three sides of a square to get to the Archives.

Side gate

By this time, I was desperate to go to the loo. And, of course, the Archives are geared up to receive visitors arriving from the Kew stop—so I still had a long walk around the entire building. I looked on my map and saw there was a service lane down my side of the building. Surely there was a side gate?

I took the risk.

I paced down the lane and, sure enough, there was a gate. A great big locked service gate. I stood there, staring at the building with my grandparents’ divorce papers. In between there was a gate with razor wire along the top. Looking at those layers, like one of those Japanese paintings of mountain ranges receding into the sky, I finally got it: those papers did not want to be disturbed.

As soon as I realised this, peace came over me. I took a few minutes to settle down as I realised it was going to be tough. I turned around and there it was, hidden behind an overgrown hedge—a side gate. Twenty seconds later I was inside.

Vertigo

The reading room was on the second floor. Half-way up the first flight of stairs, and—bang!—it hit me: a huge attack of vertigo that flung me hard against the wall. I had no idea where up was. I reeled dizzily around the stairwell until I could grab a railing, haul myself up to the first floor and sit down.

Those energies were in my unconscious for all of my life without me knowing it.

Once I understood they were there—i.e. became conscious of them—these ghosts couldn’t stay there. They crashed into my consciousness and I was completely unprepared for them. Twenty minutes later I was able to walk up to the reading room and reach those papers. It was the saddest document I’ve ever read.

Dealing with ghosts

This episode reinforces some of the principles from the first example, but it also sheds further light on the process.

When you’re dealing with ghosts in the closet you’re dealing with energies that are very old, very dense, very painful—and have a life of their own.

When you’re dealing with ghosts in the closet you’re dealing with energies that are very old, very dense, very painful—and have a life of their own. They want to be left alone—yet they also need to be healed.

Working with these energies, it can feel like you’re dealing with the supernatural. That’s why I use the phrase ‘living with ghosts’ as this blog’s title. Generational trauma has long been recognised in the church, where it’s called ‘generational sin’*. Church prayers to heal it almost read like medieval exorcisms.

* Deuteronomy 23:2 is an example of inter-generational shaming for sexual impropriety: “No one born outside a legal marriage, or any of their descendants for ten generations, can fully belong to the Lord’s people.”

Grace

What is also evident in this episode is grace. Peace came when I accepted the situation, and the way forward was revealed. If you consciously engage with the process, grace will manifest and smooth the bumps as much as possible. Amazing things can also happen when you succeed in healing generational trauma.

As I mentioned, my grandmother was launched out of the family in 1935 after having an affair and she landed in Cornwall—near the village of Rock.

Some years ago, through an ancestry site, I got an email out of the blue from a relative of my grandmother’s and I learned the name of the house where my grandmother lived. It was an unusual name—Trevisquith Manor. I searched for it but found nothing. Once again the old energies of family ghosts were playing hide and seek, wanting to stay concealed yet longing to be resolved.

A few months later, the phone rang at home one evening. My wife answered it and called out: “Some friends are going to Cornwall for the long weekend. They have a spare room. Shall we go?” I could feel my mouth forming a question: whereabouts in Cornwall? Before I even asked it, I knew the answer: Rock.

Just In Time

By then, I was an old hand at generational trauma. I thought, “OK, here we go.” Like a long-delayed appointment, I could feel it coming. I knew it was going to hurt as the ghosts came to light. And I knew grace would walk me through it.

But I didn’t know where the house was. My background is in manufacturing software, and one of the principles there is called Just In Time—that you only make something right before you need it. Just In Time applied here too.

The night before we left, I went back to the email with the house name. And I noticed something I hadn’t noticed before—some spelling errors in the email. So I searched some variations of the house name—and there it was: Trevisquite Manor, near Rock, in a 1950s council document bearing my step-grandfather’s name.

We drove up to the village and parked about 20 yards from the house. I got out of the car and straight away I felt it—a wall of pain literally holding me at bay.

Triggers

This brings me to another principle: watch for triggers.

Triggers are events that activate our buried traumas. We each have different ones. My trigger here was geography, as was going to the National Archives. Getting close to where the action happened brought those feelings to the surface. Another trigger might be a name. Or, if you’re dealing with repressed grief, you might find funerals overwhelmingly painful.

Triggers are double-edged swords. They make it easier to access these buried feelings, but at the same time they make family ghosts stronger. So watch for triggers—but often the only way you discover the trigger is by squeezing it.

What was this wall of pain that I’d walked into?

It was my grandmother’s pain. All the guilt, shame and pain of having broken up the family and lost her only daughter. She never wanted that to happen. She was just a human being struggling with a human situation; reaching out for intimacy in that struggle—and 80 years later the pain of it still affected the family to the third generation.

There is no moral high ground. As long as you think there was a right and a wrong to whatever happened in the family way back when, you won’t break generational trauma. You must forgive.

So here’s another principle: there is no moral high ground. As long as you think that there was a right and a wrong to whatever happened in the family way back when, you won’t break generational trauma. You must forgive, regardless.

As I did so, it felt like an angel picked me up and put me in the passenger seat of my own life and walked me down to the house. I felt an overwhelming sense of grace as tears streamed down my face.

Antiques Roadshow

Three weeks after going to Rock, the Antiques Roadshow—one of Britain’s most popular TV shows—was at Broughton Castle near Banbury. People display their family heirlooms; a tiny number get filmed for the show. I said, “Let’s take my grandfather’s things and we’ll have a nice day out.”

At Banbury, there was a big queue of people having their antiques assessed—and almost all of them were rejected. It took an hour to get to the head of the queue. I laid out my grandfather’s flying memorabilia.

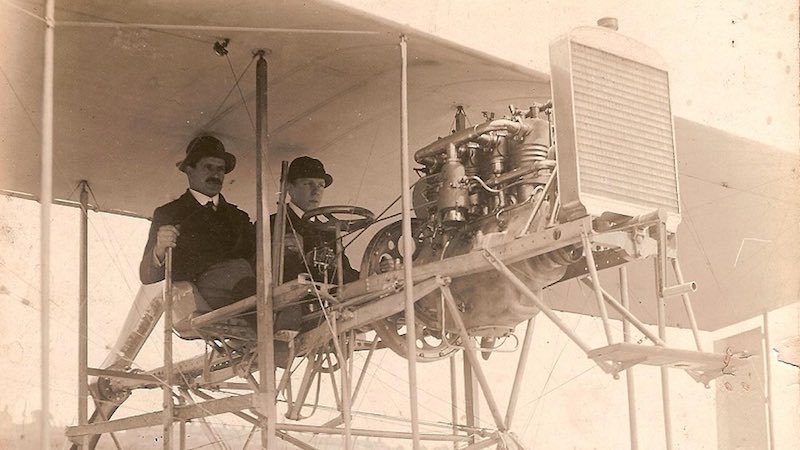

I told you that my grandfather was a pilot in World War I. What I didn’t tell you is that in 1909 he built his own aeroplane. In 1911 he got Royal Aero Club pilot’s license #79. He won an air race in 1913. In 1914 he flew the ‘first regular air service of Great Britain’. He was Britain’s first airline pilot and only the second in the world.

When the war broke out, he volunteered by the simple expedient of flying into the nearest army base (they bought his plane for £720). He won two medals for bravery and was mentioned in despatches four times. He flew without a scratch from 1909 to 1929. It’s an amazing story of one of Britain’s pioneering aviators.

Shame & sandwiches

And that’s the power of the shame of generational trauma. When I was growing up, all of this was buried. This amazing memorabilia was kept at the bottom of a drawer. The loss of her mother was so painful to my mother she couldn’t bear to be reminded of it by any sign of her father. We even moved to New Zealand—the farthest point in the world from England, as if my mother was trying to get as far away as possible from the scene of the trauma.

I showed all this to the antiques assessor. He said, “You’d better head up to the castle. The producer will come and see you. The sandwiches are on the BBC.”

Three weeks after dealing with my generational trauma in Rock, I was filmed with my family, talking about my family, on Antiques Roadshow. This story that had been buried for 80 years and even tried to hide at the other end of the world was screened in a TV show watched by millions of people.

If you choose to confront your family ghosts, I can’t promise that you will end up on a major TV show—but I can promise you a hell of a ride, and an amazing sense of healing and resolution. But please handle your ghosts with care.