While most film genres rise and fall in popularity over the decades—we are currently in a mini-age of comic book action films—one genre stands head and shoulders above all others in durability: horror. This is often attributed to its ability to allow horror fans to experience fear, the most primal and visceral of human emotions, in a controlled manner.

But what fear are we talking about? Death? Financial failure? Loss of a relationship? Discovering that the cinema has run out of popcorn? No.

Fear of the monstrous

The common element of all horror films is that they address the fear of the monstrous. From its earliest moments, such as William Selig’s 1908 version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, horror’s archetypal villains have all been monsters or, like Dr Jekyll, humans with a monstrous side. Frankenstein, Dracula, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hannibal Lecter, Ridley Scott’s Alien… the list goes on.

What’s notable about this list is that monstrosity is almost always portrayed as masculine. What is monstrosity and why is it masculine? While some find death frightening, many welcome the opportunity to die with bravery, or at least dignity. What frightens us most is loss of dignity: ridicule, cowardice, humiliation, sexual degradation.

In patriarchal societies, the sexual degradation of women is the ultimate nightmare. It demonstrates that the men have failed to protect the women—and hence the honour of the tribe—from their enemies. While it may seem far-fetched, this idea remains at the core—consciously or otherwise—of all conservative ideologies.

Shameful sex

Beyond the alien lifeforms and physical deformities so beloved of film’s early decades, at its core monstrosity is the shame of socially disapproved sex. This has historically taken many forms: homosexuality, sex across tribal or racial divides, between upper-class women and lower-class men, outside marriage, with more than one partner, anything other than the missionary position… The list is long but gradually being whittled down.

The monster represents the male attacker—whether it’s an outsider or a perverted insider—either violating women or expressing its sexual rage and disgust by murdering them.

The horror genre reduces all of these socially shameful forms of sex to a single trope. The monster represents the male attacker—whether it’s an outsider or a perverted insider—either violating women or expressing its sexual rage and disgust by murdering them.

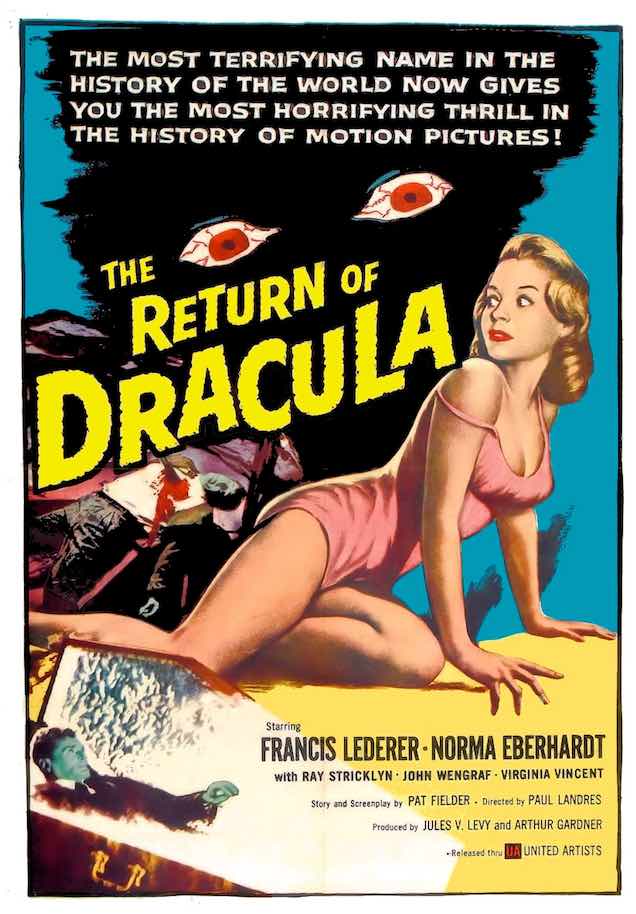

For much of the 20th century the sexual element in horror films was sublimated, with death as its usual replacement. During the 1960s nudity gradually crept in, though displays of it remain limited in mainstream horror. The poster for The Return of Dracula, a 1958 B-movie with Francis Lederer in the title role and Norma Eberhardt as the imperilled heroine, signals the key beats of the horror genre.

Every element in the poster is included with singular purpose. Dracula is largely reduced to a cipher, an amorphous background blob that leers over the heroine’s bare shoulder. The dead man with a twisted face and a knife in his chest signals Dracula’s status as a monster who has the force to express his impulses with impunity.

The ultimate horror

The foreground is given over to the title (ca-ching!) and to Rachel, a.k.a. the damsel in distress. Rachel assumes the same position as a submissive primate, rear end to the beast. Her skimpy is in girly pink, as if she’s fresh from ballet class. A strap slips from one shoulder, hinting at nudity in an age when it couldn’t be put on screen without outcry.

Even more provocative is her look back over her bared shoulder, a mix of fear and curiosity. While the prospect of being ravaged by uncontained masculine energy is frightening enough, what is truly horrific—from a patriarchal perspective—is the thought that Rachel might enjoy a good romp.

Even this publicity still of the film’s two leads, Francis Lederer and Norma Eberhardt, mimics the poster. Lederer (Dracula) leers over Eberhardt’s (Rachel’s) shoulder while one of her dress straps dangles tantalisingly off her shoulder. Eberhardt’s look contains fear—but not revulsion or horror.

Sexual purity

The more permissive 1970s saw the rise of ‘sexploitation’ horror films that traded on the increased acceptance of on-screen nudity to put naked heroines in front of B-movie fans. Prisoner of the Cannibal God (1978), starring Ursula Andress, is typical of the genre—as is its poster.

The composition is little changed from The Return of Dracula two decades earlier. The monster is a background blob. An inset detail shows the helpless heroine being carted away, leaving the foreground to the female lead. Little has changed here, either—except her breasts are larger, curvier, the nipples visible. (By contrast, the sexual content of Prisoner of the Cannibal God would’ve been scandalous in the 1950s.)

The heroine’s aroused nipples show the subtext of the horror genre remained unchanged. The mingled fear and fascination that off-limits sex might be more exciting than what was happening in the bedrooms of middle class, white picket fence America. That’s the look in Norma Eberhardt’s eyes. Horror films uphold patriarchal notions of sexual purity by putting women in situations where that purity is at risk.

With the ongoing march of female sexual empowerment—slut walks, the #freethenipple and #underboob Twitter campaigns—sexual shame is finally on the wane. It will be instructive to see the impact of this on both the content and popularity of the horror genre.

Image: Poster for Prisoner of the Cannibal God (New Line Cinema, 1978)