The slippery slope – multi-generational family fragmentation

- 11 November 2025

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Generational trauma ,

A simple, sepia-toned holiday snap from the 1920s or 1930s, probably a seaside hotel somewhere in south-west Britain. Who took it? Probably my grandfather Charles. What the photograph doesn’t convey is that a fracturing has taken place—a fracturing that the participants are desperately—albeit unconsciously—trying to paper over. The image captures the slippery slope of multi-generational family fragmentation.

The fracture is only evident when we learn that the woman with a protective arm around the boy, my father, is not his mother. It’s his grandmother Frances. His mother died from tuberculosis in 1926. Frances is ‘picking up the slack.’ She couldn’t hold it for long.

Unravelled

In the decade-and-a-half between 1926 and 1940, Charles’ life unravelled.

As I describe in “They should be out looking for my father”, Charles remarried in 1930 and moved to Bristol. Sometime over the next few years he fell out with his father. He was disinherited in 1937.

The second marriage failed and, probably around 1940-41, Charles walked out. He spent the next decade until his death in south London, living with a woman who claimed to be his wife. He never contacted his actual wife or my father again.

I now see that the pattern which began with Charles repeated at an earlier age with my father and, by the time I was born, had become genetically entrenched:

- Charles’ gradual loss of cohesion/community, eventually leading to disappearing

- My father experienced this as a child, it became the pattern of his adult life

- I experienced it from conception; it replicated in childhood and adulthood

This is a slippery slope that’s difficult to identify and even more difficult to reverse.

What is the slippery slope?

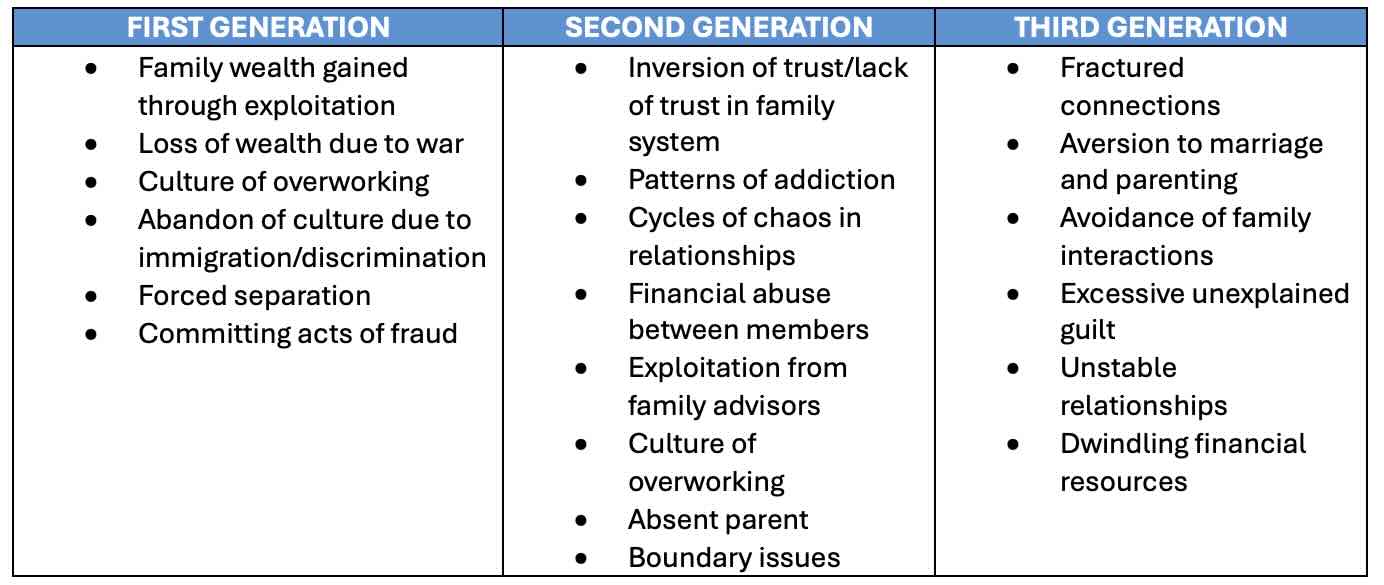

In Inherited Trauma and Family Wealth, Ruschelle Khanna describes how trauma can both replicate and mutate over multiple generations:

© 2024 Ruschelle Khanna, LCSW. Used with permission.

I can tick off quite a few of these. Some I could move into different columns. We tend to either repeat or reject our parents’ problem patterns. A child may react to an alcoholic father either through imitation or through a deep aversion to alcohol. Abandonment is cyclical, not singular.

I see repeated iterations of migration and reinvention (new identity, community, job) that never quite work out. As the shame mounts, so does the pressure to move (again).

Charles moved from Wales to Bristol to south London. My father repeated this on a grander scale, taking us from the Channel Islands to Switzerland, France, and finally New Zealand. I heaped my own migrations on top of this, while my brother resolutely stayed put.

Can you identify any patterns of repetition or rejection in your own family?

Snakes & Ladders

The slippery slope is like losing a game of Snakes & Ladders. The fragmenting family finds itself sliding down various snakes while the ‘ladders’ we use to construct strong and stable lives are increasingly inaccessible:

- Community ladder

- Education ladder

- Career ladder

- Property ladder

- Investment ladder

As the capacity to role-model strength, stability and growth diminish, so does the family’s capacity to function as a stable, supportive entity, plugged into a community and other avenues of support. Those with the least support have the least idea where to find support.

Yet the story doesn’t have to end badly.

Recognising and releasing generational trauma is the pathway to arresting the slide and, with persistence and hard work, gradually building ladders to stability and success. The slippery slope can be turned around.

Next steps

For further resources on generational trauma, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Photo: Hallett family