Vocal intonation – a secret giveaway of trauma

- 21 June 2025

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Generational trauma ,

In Character Analysis, Wilhelm Reich writes: “It is not what the patient says and does that is indicative of character resistance, but how he speaks and acts” (Reich’s italics). Here are three ways how people speak reveals underlying trauma: monologues, avoidance, and, perhaps the most telling, intonation.

Monologues

“They began to talk, and they talked without stopping as if they were afraid of stopping and feeling something… people feared silence more than anything else.”

In In Search of the Miraculous, Russian philosopher P. D. Ouspensky tells the story of a dinner guest who arrived, spoke incessantly and then left, thanking his hosts for a “very interesting conversation.”

Have you noticed that some people break into uninvited monologues, totally oblivious that they are dominating the ‘conversation’? There is little or no real dialogue. Look closely—the person isn’t really present. They’re just spewing out words on autopilot.

These monologues can serve one or both of two purposes:

- Smothering a fear of silence, as Ouspensky identifies

- Temporary relief of a desperate need to be heard

As Ouspensky notes, silence can be frightening because if we remain silent for long enough, repressed thoughts and feelings can percolate to the surface of life, giving us difficult insights, dilemmas, and responsibilities.

The guest leaving and thanking his hosts shows the temporary relief of feeling heard. Someone who has grown up without feeling that they have a voice can talk incessantly and still feel not heard—without being aware of either their actions or feelings.

In coaching situations, I look for the drivers behind the monologues and go from there. Outside coaching, I refuse to enable this behaviour and talk over them until they stop. I have never yet seen anyone come out of one of these monologues, recognise their behaviour, and apologise for it without being told it’s what they were doing.

Avoidance

The second trauma giveaway, avoidance, surfaces when we say something that the listener unconsciously finds uncomfortable but cannot consciously articulate it.

When this happens, they may deploy various strategies to end their discomfort:

- Unanswered questions: In written communications questions can simply be glossed over; if the same question is avoided twice, it may be avoidance

- Change of subject: A sudden, unmotivated and oblivious change of tack, often followed by a monologue (to prevent a return to the old subject)

- Agree and exit: Apparent interest, agreement to pick up this thread later, perhaps an empty promise to arrange a follow-up

Asking a direct question can be met with a non sequitur (doesn’t follow) response of which the speaker is oblivious. Look for people who routinely promise to take an action, such as getting in touch, then fail to do so. Sometimes, “See you soon” is a kiss-off, not an invitation.

Avoidance is usually accompanied by a tell-tale style of intonation.

Intonation

“In linguistics, intonation is the variation in pitch used to indicate the speaker’s attitudes and emotions, to highlight or focus an expression…” (Wikipedia)

When people speak consciously, their intonation has distinct qualities. Regardless of pitch variation, it is bright, present, and focused.

When someone is triggered and unconscious programming takes over, these qualities are reversed. Intonationbecomes smoky and husky, lacking presence, as if someone else is speaking through them from far away.

Once we recognise these trauma-inflected intonations, as Ouspensky notes, we acquire a new and highly accurate data source:

“When a man is chattering or simply waiting for an opportunity to begin [a monologue] he does not notice the intonations of others and is unable to distinguish lies from truth. But directly he is quiet himself, that is, awakes a little, he hears the different intonations and begins to distinguish other people’s lies.”

“Lies” refers to monologues, evasive answers, non sequiturs, fake agreement, empty promises and other manifestations of the unconscious.

Recognising these signs of trauma allows us to treat more securely, whether we are working with traumatised clients or in the wider world of work, friends and family.

Next steps

For further resources on generational trauma, both free and paid, please click on this image.

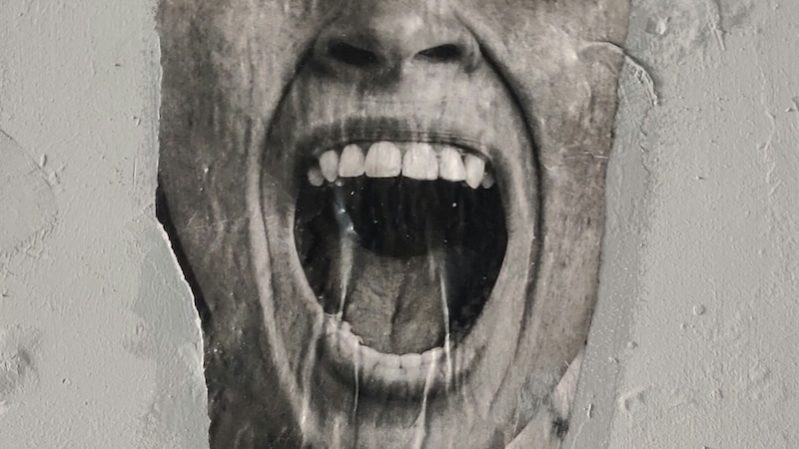

Photo by Thiébaud Faix on Unsplash