Hieroglyphics, hemispheric dominance, and polarised thinking

- 3 November 2023

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: History ,

In the 1820s, French philologist and orientalist Jean-François Champollion made a critical breakthrough in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. This mostly forgotten event provides us with a clear example of the effect of hemispheric dominance—the pre-eminence of left-brain, intellectual functioning—on the way we see and relate to the world.

Hieroglyphics

In 1799, members of Napoleon Bonaparte’s military campaign in Egypt found the Rosetta Stone—a stone containing the same text in three languages: hieroglyphics, Demotic (a later Egyptian script), and Greek. At that time only Greek was understood. It was hoped to use the Greek text to translate both hieroglyphics and Demotic.

Yet early efforts foundered. Scholars who studied the Rosetta Stone disagreed over whether hieroglyphics depicted sounds or ideas. Wikipedia describes how, building on work by the English polymath Thomas Young, Champollion synthesised both views:

“In the early 1820s Champollion compared Ptolemy’s cartouche with others and realised the hieroglyphic script was a mixture of phonetic and ideographic elements.”

(A cartouche is the inscribed oval in the middle of the picture above.)

Blind spots

What was it that allowed Champollion to make this breakthrough?

A child prodigy, by the time he was a young man Champollion spoke Ancient Greek, Arabic, Coptic, Hebrew, and Latin. This demonstrates a remarkable ability to absorb knowledge, yet it doesn’t explain the critical element.

The difference between Champollion and the others poring over the Rosetta Stone was that he saw the jigsaw puzzle as a whole while they assumed—wrongly, as it turned out—that the pieces fitted EITHER one way (phonetics) OR another (ideographs) but not both.

What caused the other scholars’ assumptive thinking, and Champollion’s lack of it?

For whatever reason, Champollion’s mind was less affected by hemispheric dominance. He had a full field of vision, while they had blind spots—and were ignorant of them.

Hemispheric dominance

Neuropsychologist Roger W. Sperry first proposed the theory of hemispheric dominance in 1960. He received the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for this work, though some aspects of it are still questioned.

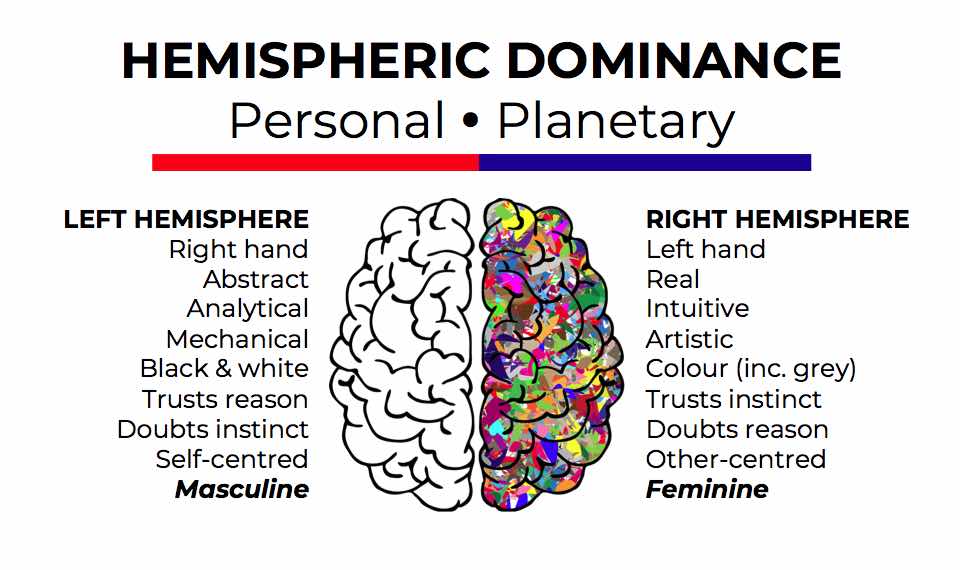

In my own simplistic terms, it boils down to three interlocking principles:

- Brain functions are specialised between the left and right hemispheres.

- Intellectual processing occurs in the left brain.

- Most people are left-brain dominant.

The left hemisphere is intellectual and divisive. Its axis is vertical—the axis of separation. The right hemisphere is intuitive and additive. Its axis is horizontal—the axis of inclusivity.

Because of its divisive nature, left-brain hemispheric dominance perceives in terms of either/or. Everything is this or that, positive or negative, good or bad.

In Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) this is called ‘black and white thinking’, ‘absolutism’, or various other names. All highlight an unconscious bias for this-that division and a mental inability to synthesise.

Seeking enemies

The problem with either-or thinking is that it promotes division—it seeks an enemy.

Historian Gordon Rattray Taylor writes of “the familiar psychological process of decomposition. Since it is difficult and painful to feel conflicting emotions of love and hate at the same time, it simplifies our emotional situation if we can divide people and things into wholly good and wholly bad.”

Former U.S. President George W. Bush epitomised this mentality with his war cry, “You’re either with us or against us.”

As I write this in November 2023, the Middle East is once again in turmoil. Notice how much people are polarising between pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian camps. Hemispheric dominance is much in evidence, spewing outrage and perpetuating cycles of violence that have no beginning and, seemingly, no end.

What price a Champollion for the early 2020s to decipher the hieroglyphics of genuine Middle Eastern peace?

Photo by Tom Podmore on Unsplash